Rinat Reisner-Podissuk

Artist

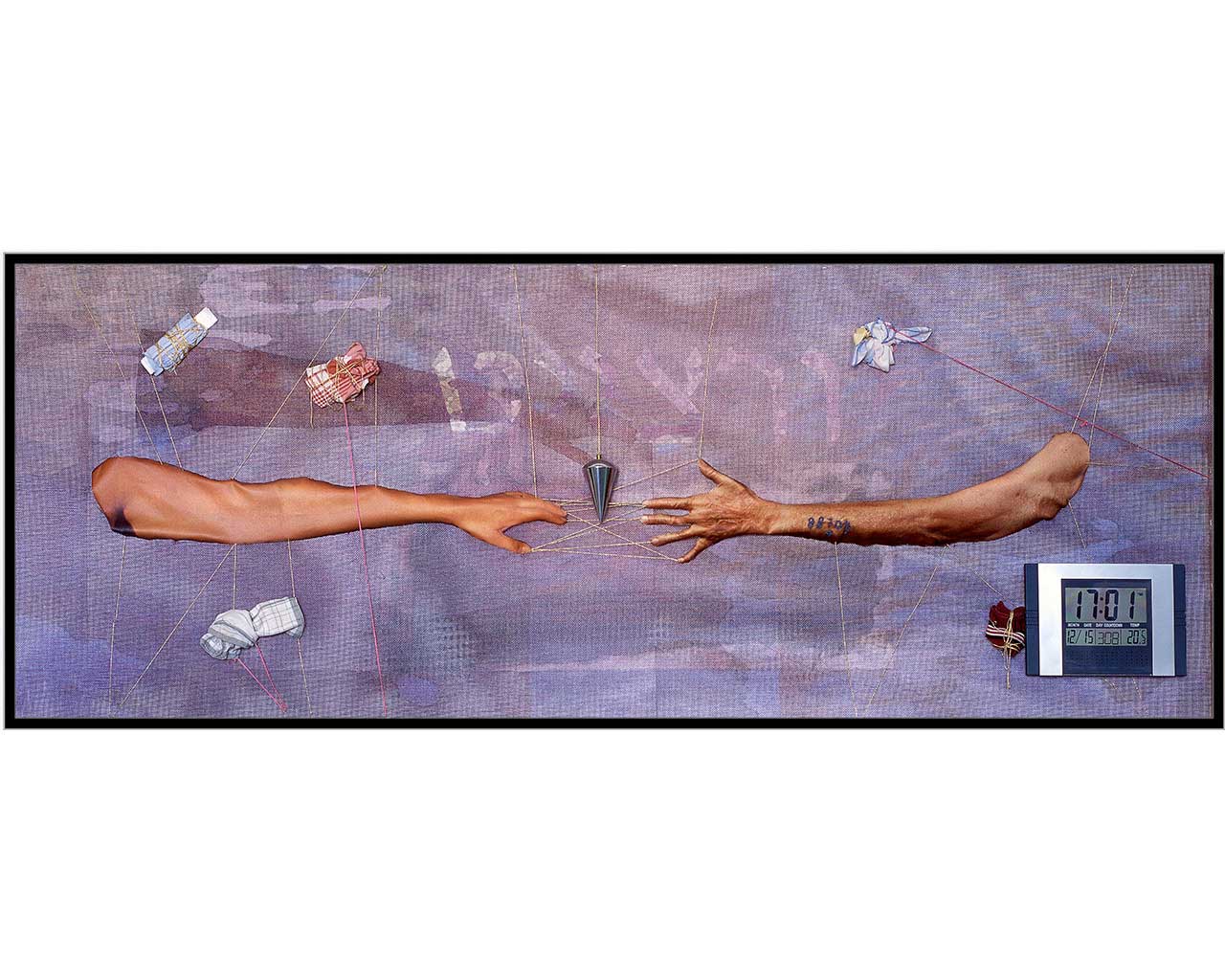

yearzeit

- Year:

- Materials:

- Size:

Yahrzeit

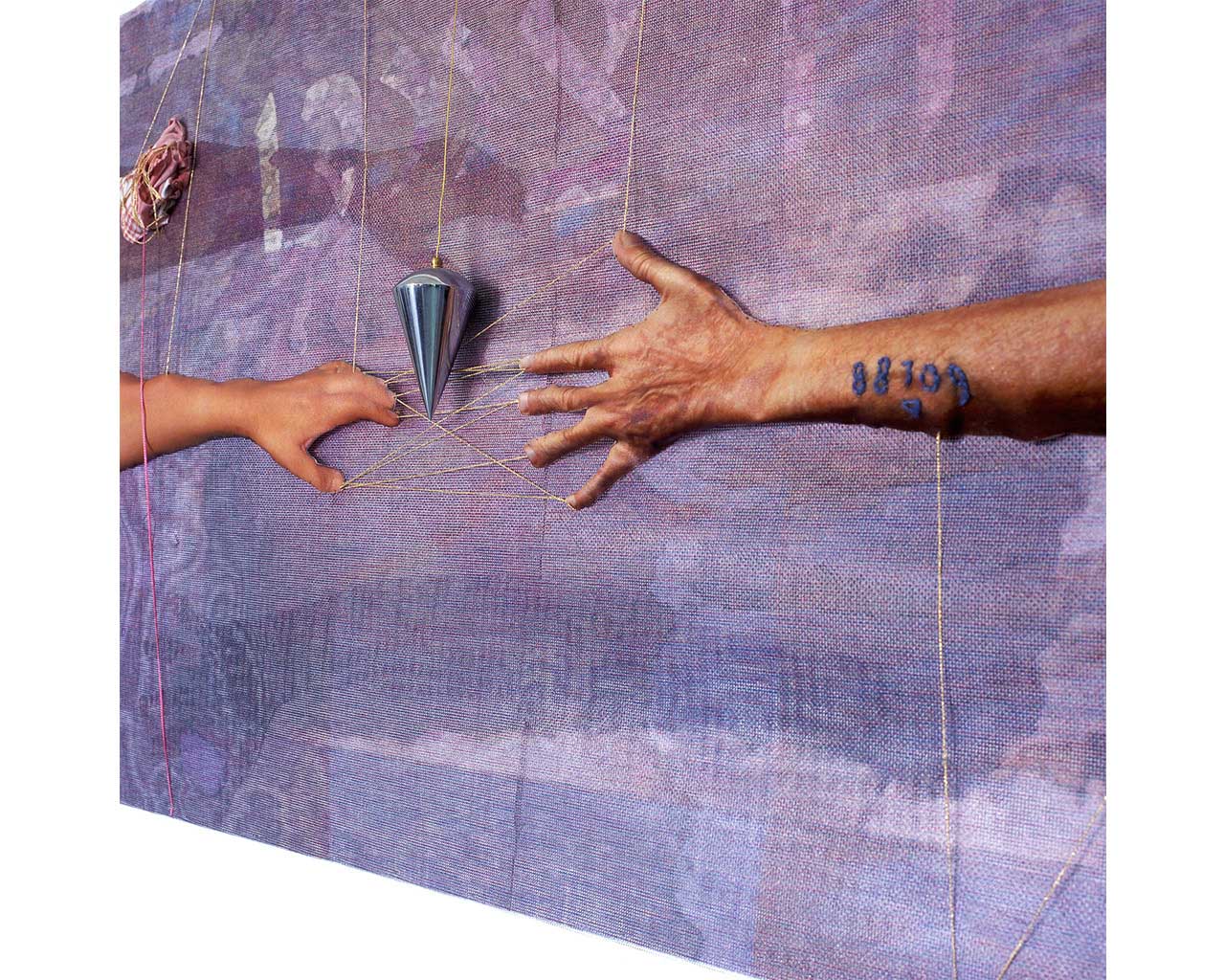

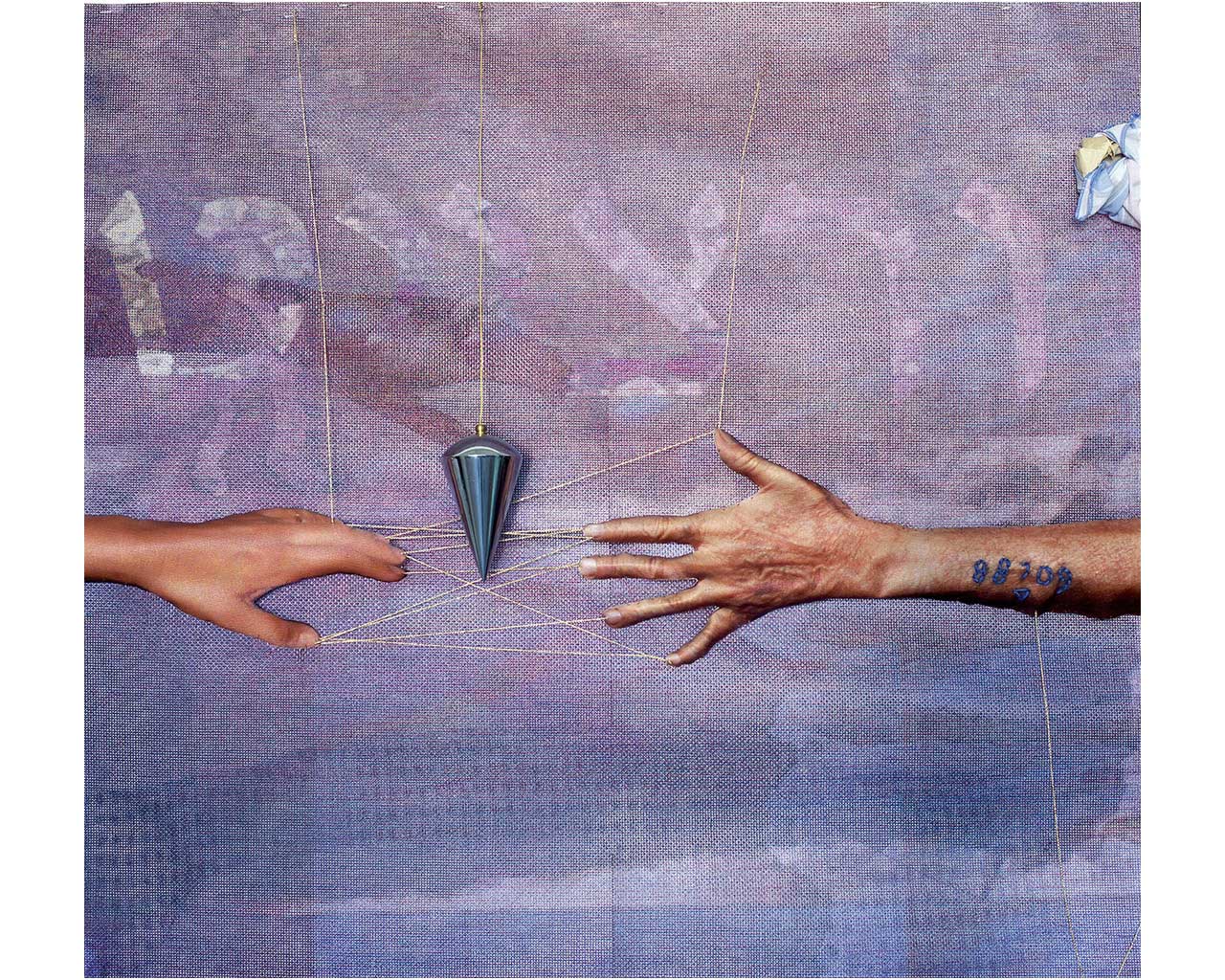

The work “Yorzeit” serves as a farewell from my father Zelig Podissuk, and a whole generation of holocaust survivors: “the people with the numbers on their arms, who I remember so well from my childhood.

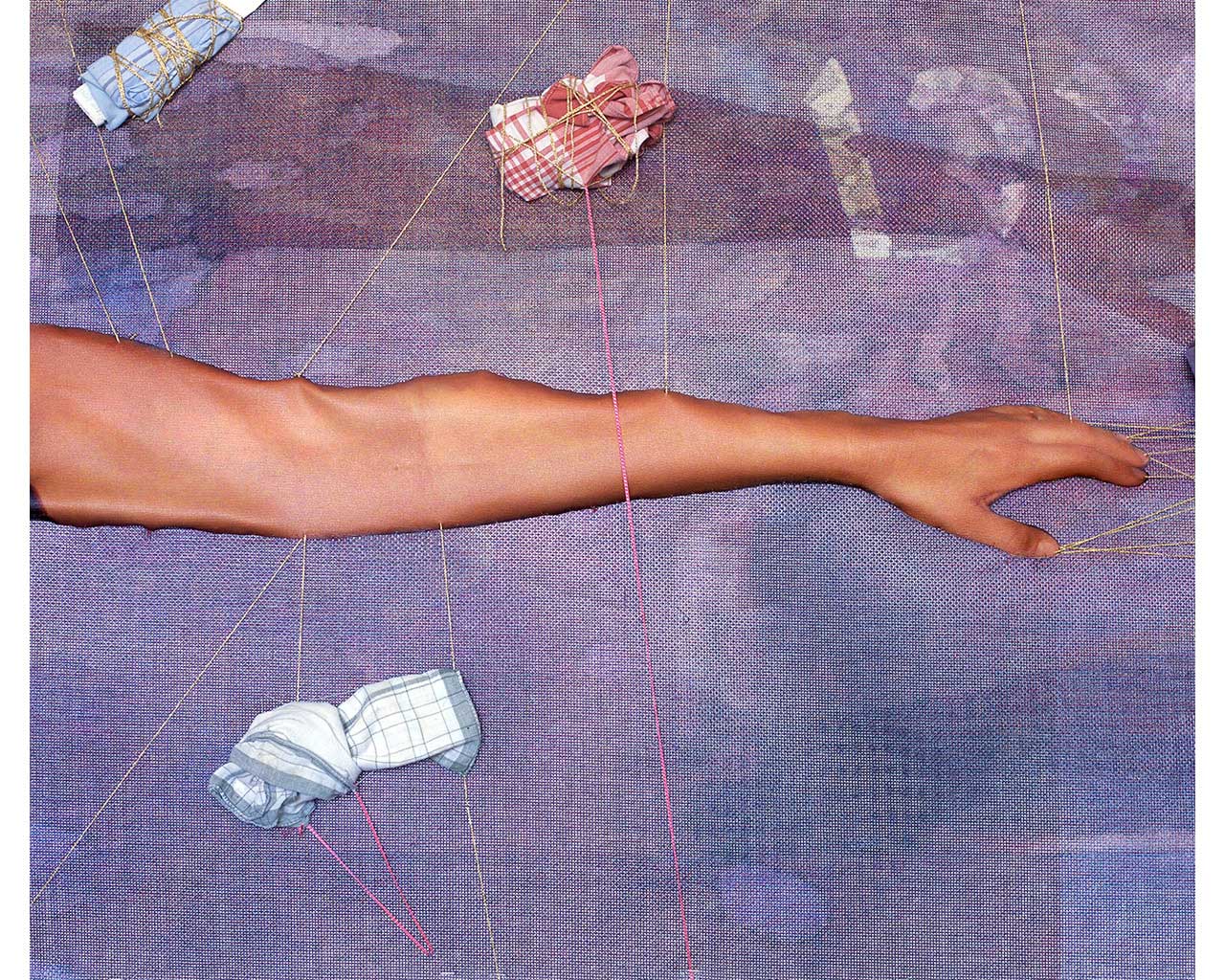

My works are built as a series, and as triptychs. They always take the form of a journey, and relate to the search for a place where I will feel an affinity. This is in fact a journey in search of identity. The place where I feel this connection will answer the questions of my identity. The scene, which expresses my search, freezes, hotographs the place, and continues onward in search of other places. In the drawings that I paint, which describe the places that I find, I, and the viewers are able to remain in the place, but the search will always continue. I paint the places on small canvases, as if they were postcards, a collection of memories. Usually I suitcase, which enables quick movement from place to place, as if I was the wandering Jew, or as if I was my father, who traveled around Europe for 8 years until he reached Israel, and also here his journey did not end.

It is impossible to build a continuous identity when there are missing links. My father hid his past from me. He denied me the opportunity of getting to know him. There were details that were revealed to me , but my father broke their continuity, and I was unable to construct his full story. It is difficult to make contact with a father when there are so many things you don’t know about him.

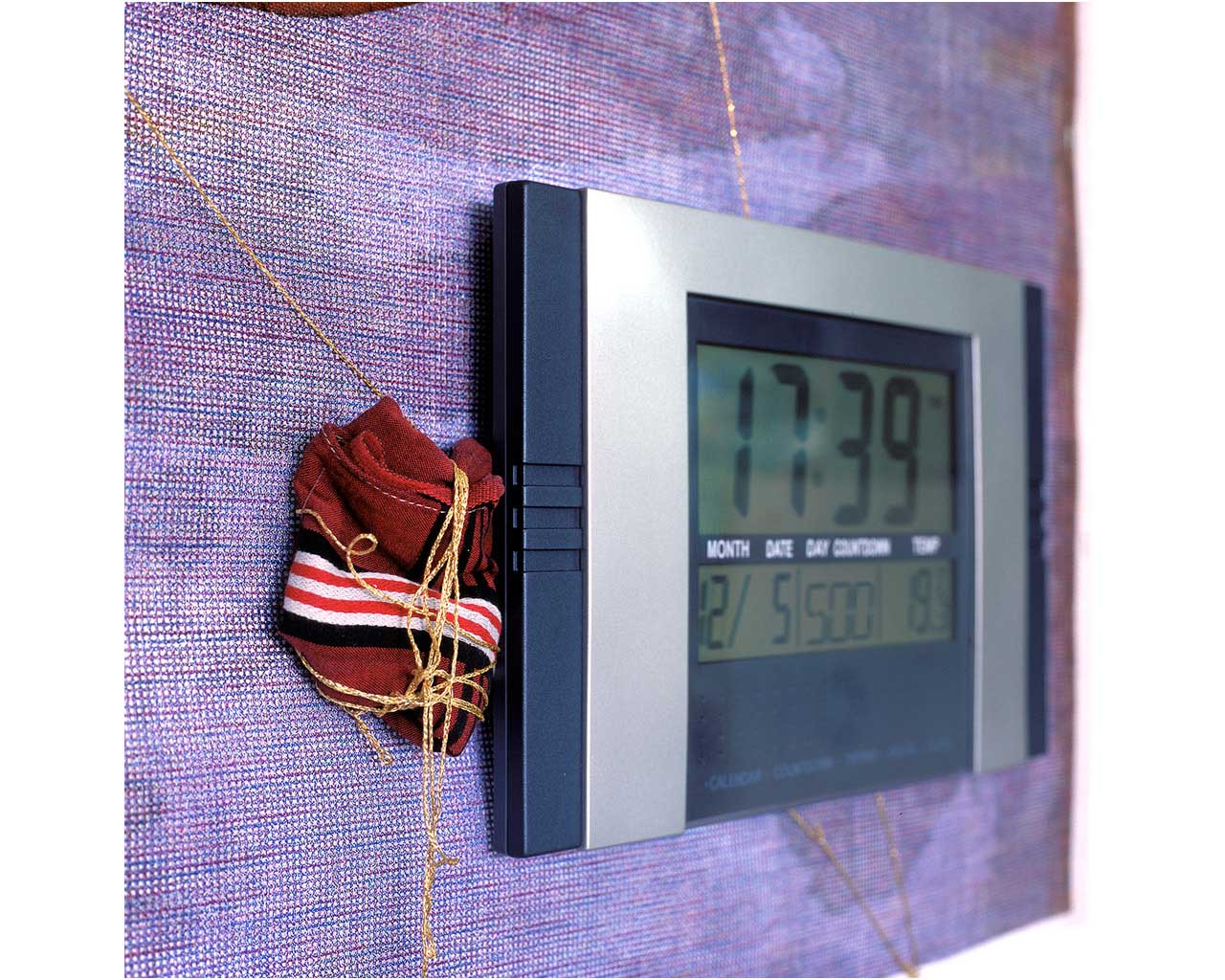

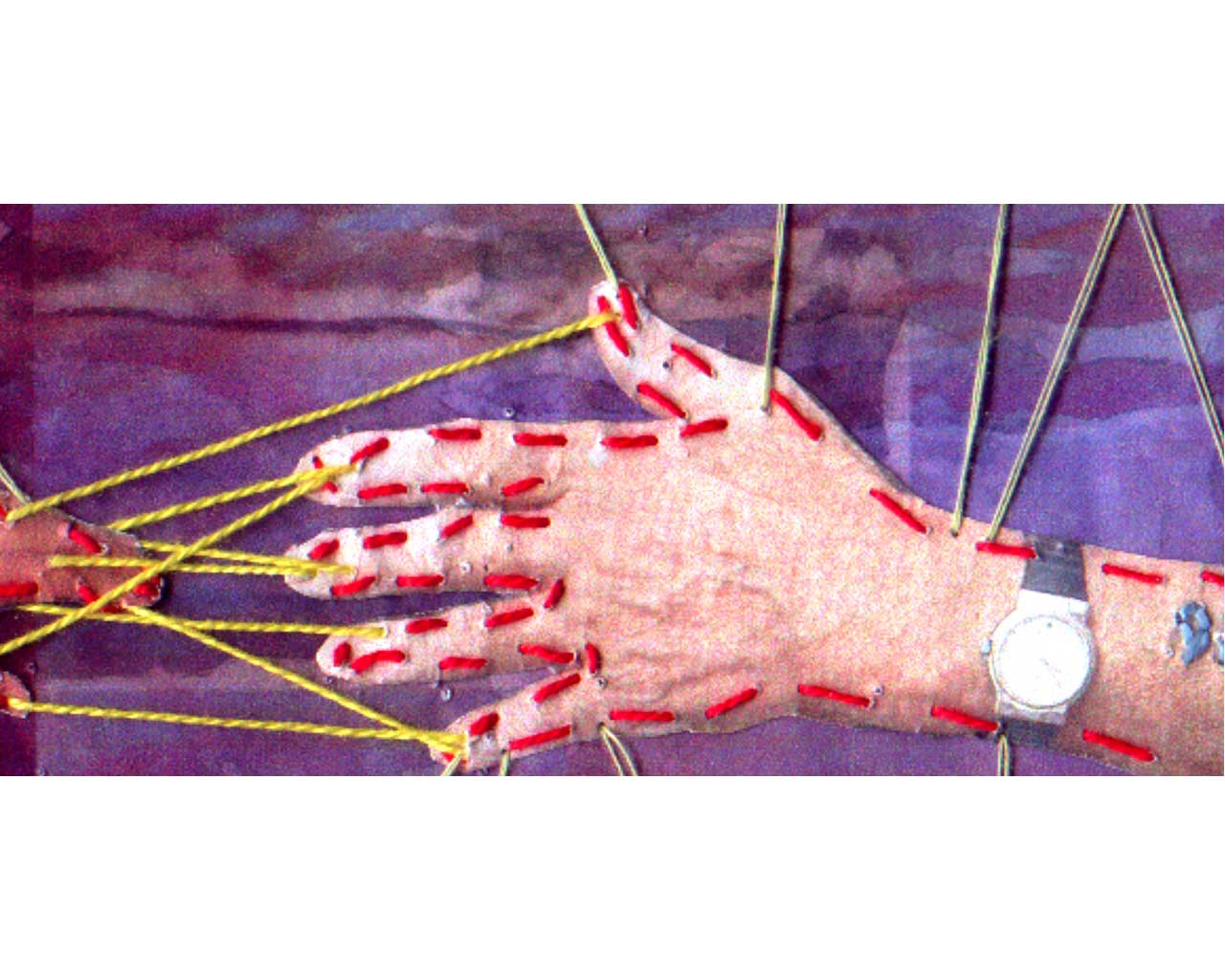

When my father died a year ago, I slowly began to find the missing links. I found pictures which I had never seen – photographs of places which I never knew he had visited. I arranged a picture album for him for the first time. I met people who told me about him, and his past, and he was no longer there to interrupt. I met people from the small town in which he grew up, and I discovered the meaning of my family name, Podissuk which is a rare name in Israel : the name of the district in which It’s a paradox – on the one hand his death left a huge vacuum, yet on the other hand, now, after his death I am able to try and make contact with him. This attempt is displayed in the work “Yorzeit” where the threads attempt to make a connection between all the elements in the work, and the hands search for a way to reach each other.

The first work which I dedicated to my parting from my father, was a paper chain, like those we use for decoration on the holidays, in which there would appear alternatively pictures of my family as a young girl, and pictures of my family today as a mother – the chain of connection and identity which passes from generation to generation.

“Yorzeit”, is as such a parting from my father. I was born in 1966- when I was born my father was 56. I grew up in Tel Aviv – the “big” city, the city of the bourgeoisie, the middle class, where many of the residents then came from Eastern Europe. From my childhood I remember the people with the numbers on their arms. Already before I could understand the meaning of things, I understood from other adults that I shouldn’t ask questions – that it’s connected to something terrible. I understood that I shouldn’t get close to them, that I would never know about them, and the “people with the numbers” won’t tell me anything. Today I know that in every place in Israel the number on the arm was a code for identifying, and social isolation. In the streets of the city “the crazy people of the holocaust” as we called them, wandered around. There was one who was tall and thin, always dressed in short pants and high boots summer and winter. He would march forward swiftly, and suddenly stop, raise his arm forward and shout “heil Hitler”. At that moment we would run terrified into the shop openings. We felt his fear and madness long before we understood the reality of what Hitler had done. Another “crazy” holocaust survivor would stand on her balcony and spit at whoever walked past.

Another wandered around with two suitcases, would stop in the middle of the intersection and wave his hands – we thought he was reading the stars! As children we understood that something dreadful had happened to these people. Most of adults around us were not born in Israel. They all knew additional languages, and dressed differently. My father always wore a suit and hat, when those born in Israel (sabras) wore short pants and sandals. People like my father brought with a spirit of a different place. I repeat, and emphasise- the message was that one must not ask, yet with this one must not fear. The message was not given openly, but unconsciously, using gestures of speech, hand movements, silence and My father told me very little of his past, but his past and life experience penetrates deeply into my life at all times. My father was born in 1910,on the border of Russia and Poland, and he experienced three wars, as he would say – two world wars and the War of Independence in Israel. During the world war he served in the Soviet army, and after the war he wandered around Europe for a few years, and came to Israel in 1948. My father didn’t talk much and didn’t relate stories – I know nothing of his life as a child before the war. I don’t know why he didn’t marry for so many years. It was important for him to teach me about “life”, and as he spoke so little, he passed on his conclusions, summarized and as a doctrine – as a body of knowledge, not to be queried. Most of this was handed on to me in an unconscious way. He would say: “what could you possibly know about life?” and it was clear to me that life was too large for me. After he died, and the ban on his past was lifted, I started to examine within myself what things I got from him, what approaches to life I adopted, without knowing. And here are some of Survival and the meaning of life: Life has always been to me something one relates to very seriously. One doesn’t live without purpose, doesn’t enjoy aimlessly- that would be senseless, as my father would say ————————. Life is something

one should prepare for – to look 10 steps ahead, to be prepared for any change that appears, and to adjust accordingly. When the last intifada broke out in 2000, I saw within myself the ultimate of my father’s inheritance: I was in a state of panic and confusion. Perhaps this was the situation I had been prepared for for so many years? Perhaps everything is going to be destroyed and he who is clever and will act smartly will be saved? Is this the same situation that my mother’s family was in in Germany in 1933 when they realized that this is the time to leave and be saved? I immediately set into action. I was in advanced stages of selling my apartment, and transferring the money to foreign banks, and getting prepared to leave at any minute. I just wanted to protect my family at all costs. At the last moment I realized that I was acting irrationally, and that the danger was not so great. Instead I cancelled the subscription to the daily newspaper and distanced myself as far as possible from the confusion that was occurring in the country.

There are several layers to reality: This is another inheritance from my father and that generation. There are several layers to reality, and one can only live part of them – like those holocaust survivors who continued their lives by closing off their past within themselves and living in denial.

In the same way, I also continued to live my daily life without relating to what was happening around me. The survivors who closed out their past, out of difficulty to touch it , or for fear of hurting their close ones, carried within them heavy guilt feelings for having survived. Shabtai, my friend from the organization of Greek survivors, would repeatedly say to me : You see who has survived? These are the simple folk who knew how to steal and to succeed in life – the intelligent ones went……

Another element of survival was money. One should always have cash money and foreign currency at hand. I remember from my childhood a neighbour who wasn’t wealthy, but his pockets were always bulging with dollars, for any emergency that might arise. In the first Gulf War, my father forced me to sew inside pockets on the family’s clothes, and filled them with tens of thousands of dollars. I also got strict instructions that if anything should happen, I am not to worry about my parents, but should buy a plane ticket at any price and flee. Money is not meant for living, but for security for the future.

My father didn’t trust other people. I remember how he would instruct me: “If a friend starts to talk to you and talks too much, tell him

politely that you are in a hurry, and leave. It’s not good to speak too

much” He taught me Yiddush sayings which illustrate his approach to life………………….which means one can’t trust anyone, and…………

Which means: we don’t have much control over our lives and over others.

And as I said, the work “Yorzeit” which I am presenting here, is in memory of my father Zelig Podisuk, but it is also part of my search to uncover his world, which in turn is helping me to unravel my identity, as something separate from his.

Copyright © 2014 · RINAT REISNER-PODISSUK